Mulhouse-Nord:

a temporary exhibition

The French Railways Museum opened its doors to the public on 12 June 1971. Located in the half roundhouse of the Mulhouse North depot, the institution presented a selection of thirteen pieces of rolling stock from its earliest days. The unconventional museum drew large crowds, eager to discover it. The articles published on 13 June in local newspapers such as L’Alsace and Les Dernières Nouvelles d’Alsace greeted the technical and human adventure it represented, the fruit of efforts that had been initiated in the early 20th century.

A man. A woman. A dog. And in the background, the French Railways Museum. That could be the title of a Nouvelle Vague film, but the documentary was called something totally different, namely The Railway Enthusiasts. This little gem was aired by the French television broadcaster in 1973. It was written by Jean Jacques Bloche and directed by Yves Le Ménager, and was part of a series named “Life in Your Spare Time”. The documentary devoted to the railways portrayed Alain, a railways enthusiast, and the introduction of his fiancée Andrée to his other love.

As they go into the half roundhouse of Mulhouse North, these fictional characters meet Michel Doerr, the first Director of the Museum, wearing his signature hat. The old-fashioned labels placed before the machines provide information about the items on display. At the end of the visit, Andrée is fully supportive: “I find this wonderful, but it is all a bit still”. That was the criticism the museum founders had tried to address from the very beginning, by developing tours and animations. As Jean-Mathis Horrenberger pointed out, a new civilisation was on the march: that of entertainment.

That is the number of visitors who discovered the temporary exhibition in the half roundhouse of Mulhouse North between its opening to the public on 12 June 1971 and its final move to 2 rue Alfred de Glehn in 1976.

Mulhouse,

trains on display at last

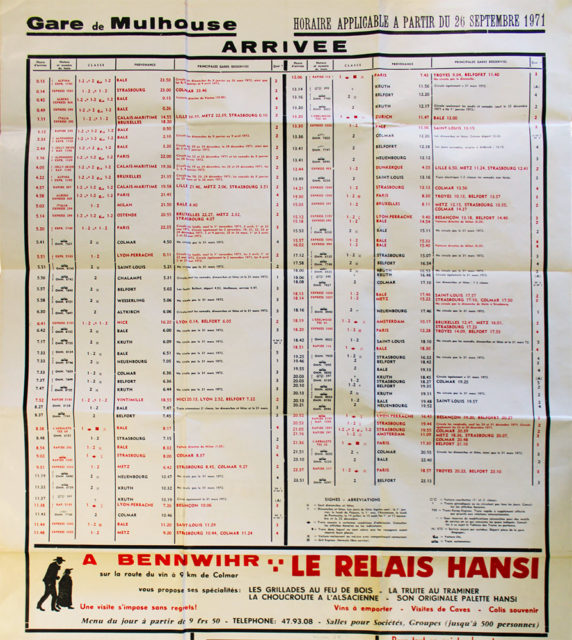

12 June 1971. 10 am The French Railways Museum finally opened its doors. 82 visitors were already there to see the temporary exhibition in Mulhouse North. That number kept growing over the day. And yet, the competition was fierce: the Le Mans race was starting with a bang on televisions across the country! Trains or cars, that was the question. As reported in L’Alsace in its issue of 13 June, two lorry drivers, Mr Frey and Mr Woelfel, happened to be the very first visitors, under the attentive gaze of Michel Doerr, in his blue raincoat.

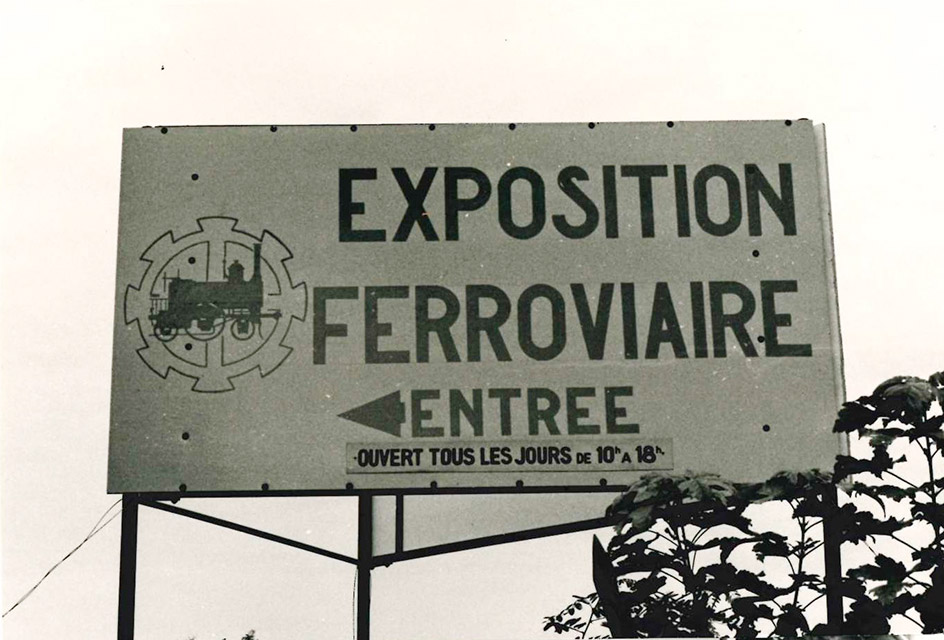

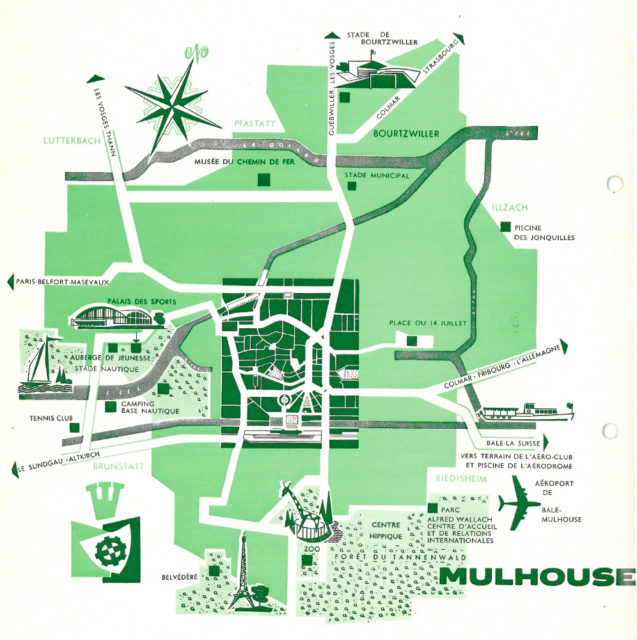

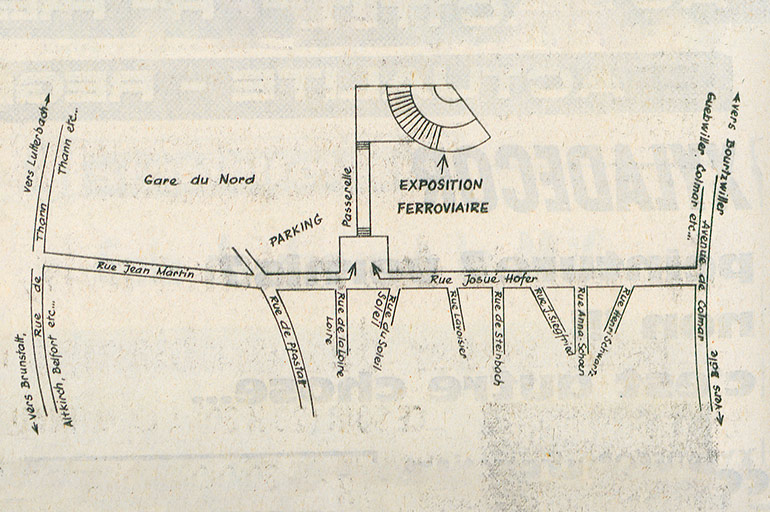

For some, the discovery of this new cultural amenity was an unprecedented experience. You parked along rue Josué Hofer or at the depot car park, and then took a footbridge over goods train tracks. In the distance, the half roundhouse announced its museum status in red capital letters to curious and resolute visitors.

On 19 June, the newspaper L’Alsace pointed out that access was not easy for those who were unfamiliar with the Mulhouse railway scene. Another access map had to be published. That initial hiccup did not last long. The museum staff soon began putting out signboards, distributing flyers and working alongside the Mulhouse tourist office and the local, national and international press. For example, five months later in October 1971, 130 German journalists had already been to the museum. Even before it moved into its permanent home, the museum aimed to make its mark on the public mind.

000001

The first museum ticket (numbered 000001) was unearthed in a bundle of archives, and is now a precious relic. Beyond its symbolic aspect, it raises an interesting question: can an object about the history of a museum itself become a museum piece? One thing is sure, much thought went into the making of this little piece of paper, 5.7 x 3 cm. Its format, thickness, colour and fonts are as many nods to old railway tickets. It was punched at the entry to the half roundhouse, and immediately carried the visitor away into the world of the railways. In that regard, admission rates were a central issue and led to a number of discussions from the very outset. In the first museum newsletter published on 4 June 1971, the idea of offering concessionary rates for children aged 6 to 15 and free admission to members of the organisation was already floated. In November 1971, the second issue informed the members of the organisation that “at the suggestion of the City of Mulhouse, the decision has been made to create a special rate for all groups (of at least 10) of school children visiting with their teachers”. Over the years, as operating costs rose, the admission rates did eventually increase. Between 1971 and 1974, the full rate went from FR3 to FR5, and the concessionary rate went from FR2 to FR3. At the same time, the categories of visitors entitled to free admission grew. The employees of French railways and the CIWL were among them.

Care and

display

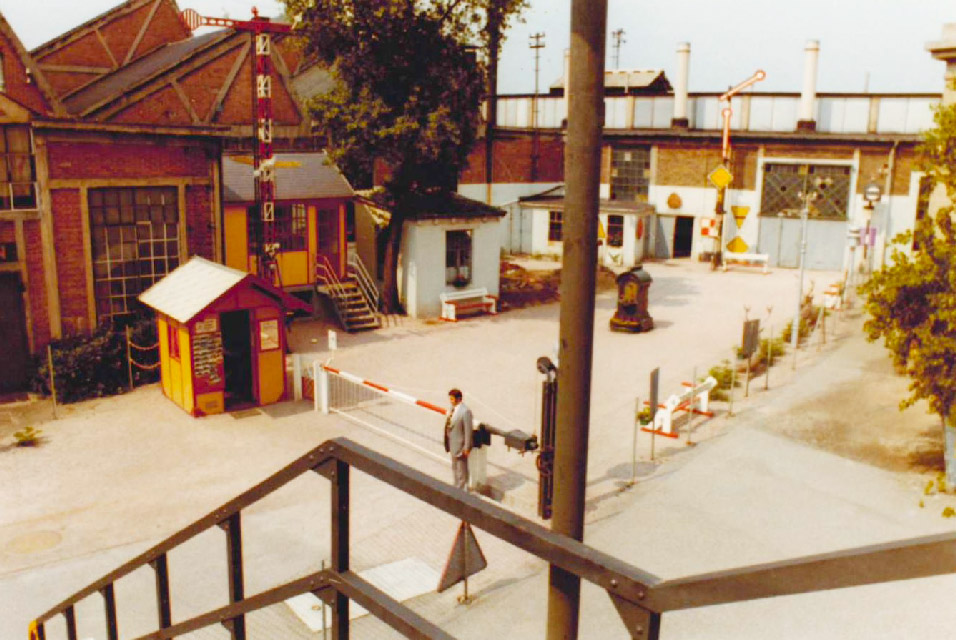

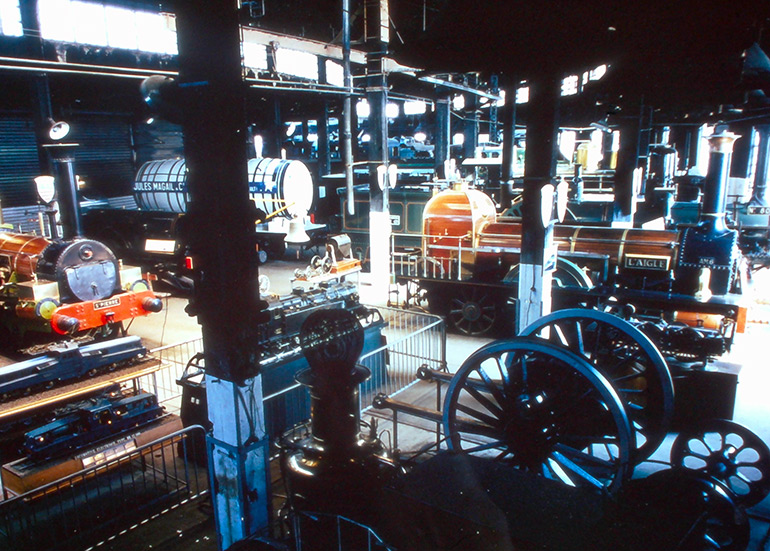

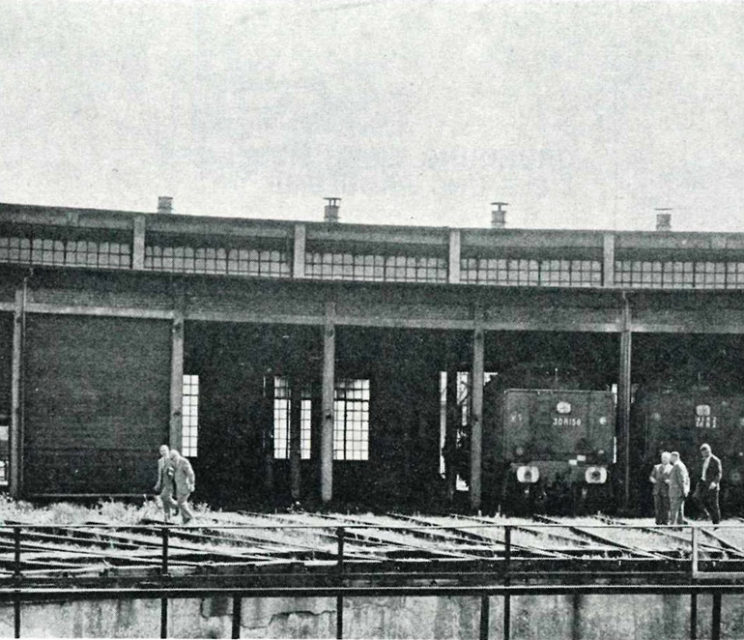

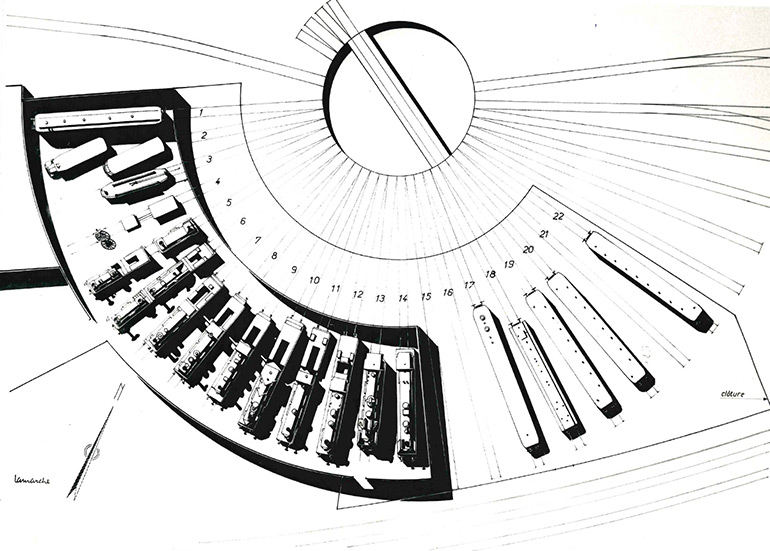

Once past the ticket office, visitors were asked to enter the half roundhouse A of Mulhouse North. The structure, built in 1923, was used for working on 141 R steam locomotives up to 1970. In September of that year, the electrification of the Mulhouse-Belfort line made it obsolete. Cleaned of its soot, the half roundhouse and its 14 tracks appeared to offer an ideal temporary solution. The individual metal curtains between the tracks and the turn table also kept the museum objects safe and secure. But as Michel Doerr pointed out in one of his letters, the new role of the building as a museum could only be fulfilled with some preliminary changes. The installation of a ticket office (former crossing keeper’s house) and a lavatory (inside a passenger carriage) were some of those changes. The museum was not just intended to house a “sample” of rolling stock, but also to put it on display for the public.

Caring for and displaying seem to have been the watchwords of the institution from its beginnings. Michel Doerr, who was keen to hire a team for maintaining the equipment, restated the need to have full-time employees, to staff the museum round the clock and round the year. In a handwritten note to Jean-Mathis Horrenberger, the Director calculated a need for 8 hours of weekly labour for each machine, that is to say 96 hours for 12”. Those employees were supplemented by guards, clerical workers, salespeople, cleaners and guides for school and other groups, which had begun to come in ever larger numbers.

“The main problem before us is that of hiring the employees that will be necessary for:

– adequately receiving visitors and supervising the museum during visiting hours, […] not forgetting merchandising, which would require the installation of stalls selling souvenirs, documents, postcards, slides and miscellaneous gadgets […]

– maintaining our large machines and the building. […]”

Michel Doerr in Musée Français du Chemin de Fer, special issue no 3 of the quarterly newsletter of the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse, 1971

Early rolling stock and partnerships

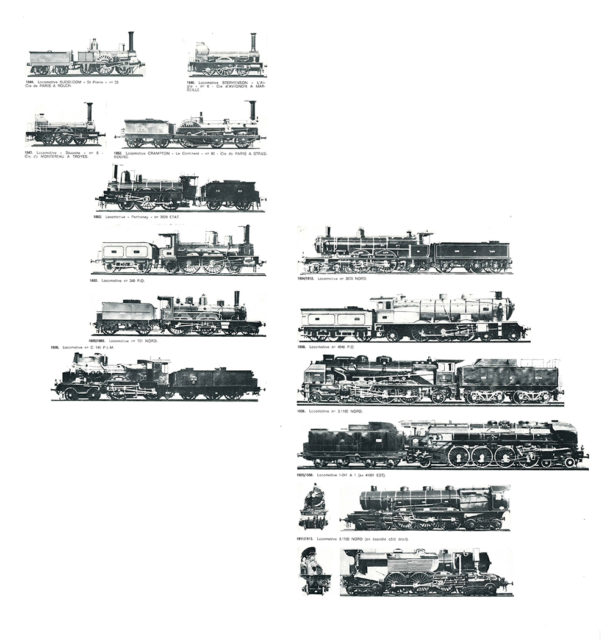

While some equipment was still being restored in the workshops of SNCF, other items were already onstage. That was true of the Forquenot locomotive, which came serenely into the half roundhouse in November 1971, hidden by protective polyvinyl. Spread over 14 tracks, the first rolling stock of the museum was listed a few months later in a document titled “Brief description of equipment displayed in the roundhouse (from left to right after entry).” For each locomotive, it briefly indicated the empty weight, drive wheel diameter and place of restoration. That early list also mentioned partnerships with AMTUIR and CIWL. The Diagram of locomotives that was put on sale provided a stylised overview of the profiles of each machine. The document below, published three years later in 1974, uses an aesthetic similar to that of natural history drawings . The collection was seen a living entity, which would continue to develop.

A museum that is the “only one of its kind”

In the writings contemporaneous with the temporary exhibition in Mulhouse North, the issue of museography was raised time and again. Indeed, the requirement was uncommon, that of exhibiting large objects in a manner that was both scientific and enjoyable. For Michel Doerr, the presentation also needed to be the “only one of its kind”, and “well spaced out”. The limited area available in the half roundhouse thus made it necessary for the museum designers to make difficult choices. Those were particularly imposed by preventive conservation issues. Some carriages, believed to be too fragile, were thus kept aside for the future final museum; that was particularly true of carriage A 151.

While steam locomotives may be displayed in a depot roundhouse, such a building is, however, a relatively inadequate shelter for significantly more delicate parts that require more careful maintenance. In view of conservation considerations, some antique carriages that have already been carefully restored in the workshops of Romilly have not been put on display in Mulhouse North. They will remain where they are for now, in better conditions (hall that is entirely sheltered from the elements, heated in the winter, with satisfactory humidity etc.).

– Michel Doerr in Musée Français du Chemin de Fer, special issue no 3 of the quarterly newsletter of the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse, 1971

Restaurant

car

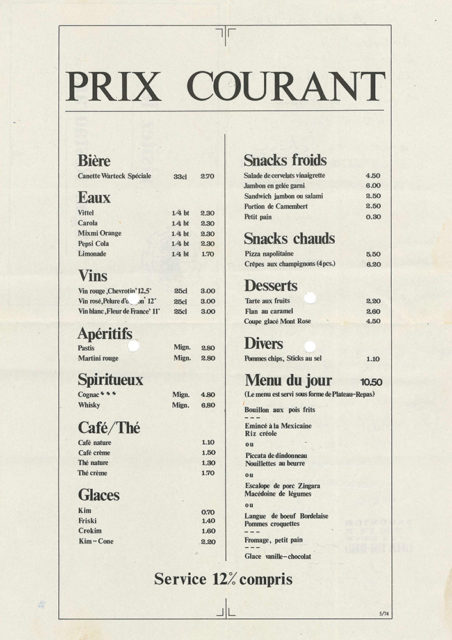

Among the trains put on display in the half roundhouse, one carriage also acted as a restaurant. In front of the museum, restaurant car CIWLT 3348 was open to individual visitors and groups, and served meals, ice cream and orangeade. This high point of the visit, which was planned as early as in 1968, offered a “user experience” to delight all ages. Carriage 3348 was sent back for restoration to the Saint-Denis workshop in January 1974 before it finally entered the museum. It was replaced by carriage 3349 in May 1974.

According to L’Alsace, you could order takeaway meals and picnic boxes, in what was described by the museum staff as a “typical railways atmosphere”.

Today, carriage 3349 is used by the chocolate museum in Geispolsheim, but is historically related to the 3348, which can be seen in the Show Tour of the Cité du Train.

Virtual tour of the restaurant car

The locomotive and the cook

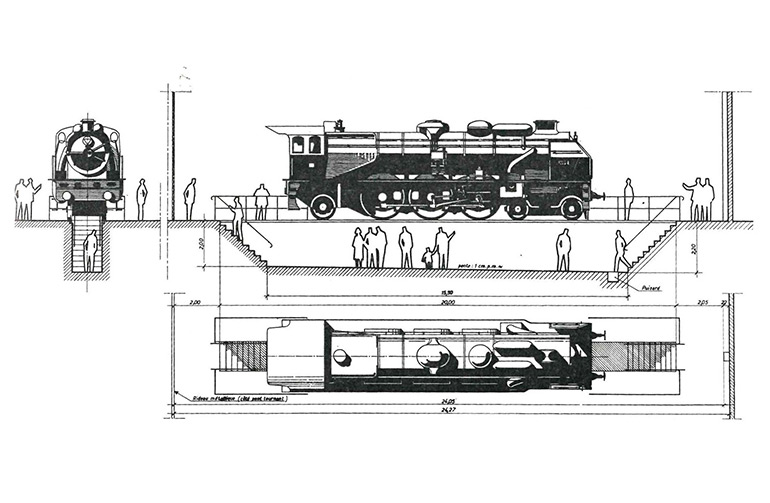

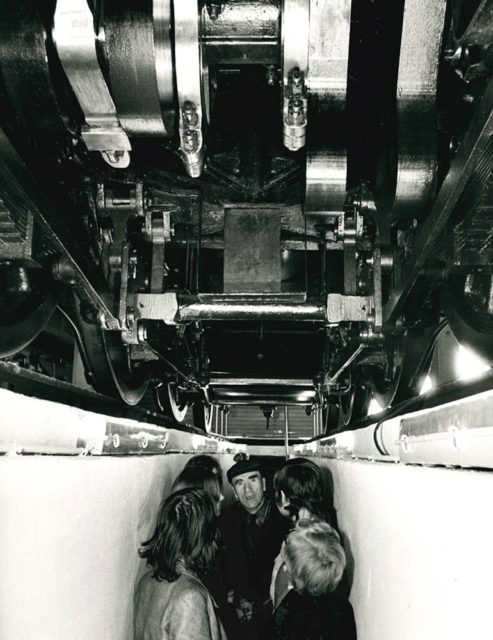

On 4 June 1971, the members of the association were informed of the imminent arrival of a “unique attraction”. Within the roundhouse, an inspection pit, almost two-metre deep, was dug under track 13 to show the inner mechanisms of the Chapelon locomotive. On 18 June of that same year, the engine was delicately moved over the empty space. Once again, L’Alsace witnessed this uncommon event and gave a very good account of it.

“The Blue Train team were furious yesterday afternoon: the diners had almost not touched their dessert – strawberries with sugar. The young chef was ready to throw in the towel. And that was because the Pacific suddenly hogged the limelight at about two o’clock. It had not moved for a week. It had been given extensive beauty treatment. All its copper and bronze – and there was plenty of it – was polished to a high gloss, in a harmonious contrast with the chocolate livery of this machine from the North. And now, with the help of two shunting locomotives, it looked like it was about to escape”.

– R.F., “The “Pacific” has been placed on its inspection pit” in L’Alsace, 18 June 1971, Cité du Train collection

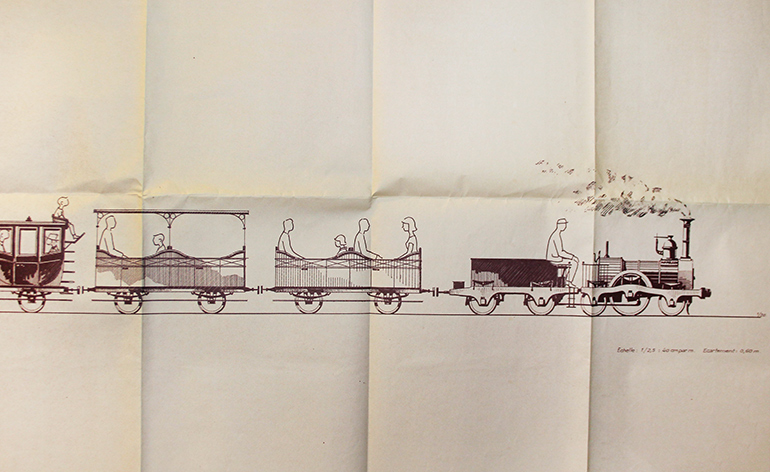

Lilliput

An undated drawing by Michel Lamarche stored in the Archives of Mulhouse shows a strange convoy. Stored between engineering drawings and administrative correspondence, these miniature train sketches imagined by the railways artist show great sensitivity and poetry. In 1970, Michel Doerr and André Portefaix nurtured the wish to create a Lilliput railway. However, while the miniature scale could take visitors back to their childhoods, it did not allow them to measure the “labour of men” according to Michel Doerr. That meant that the machine and its “engineering reality” had to be demonstrated to visitors. The inspection pit, from where the mechanical innards of the Chapelon Nord 3.1192 locomotive could be seen, helped achieve that aim.

Cards, handkerchiefs

and traditions

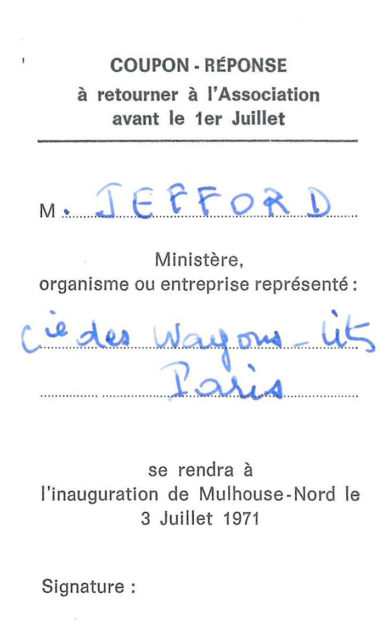

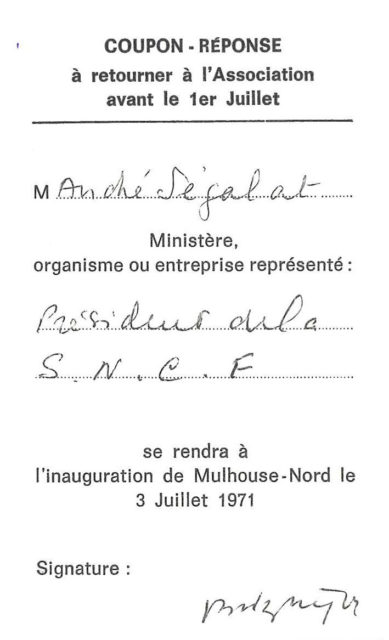

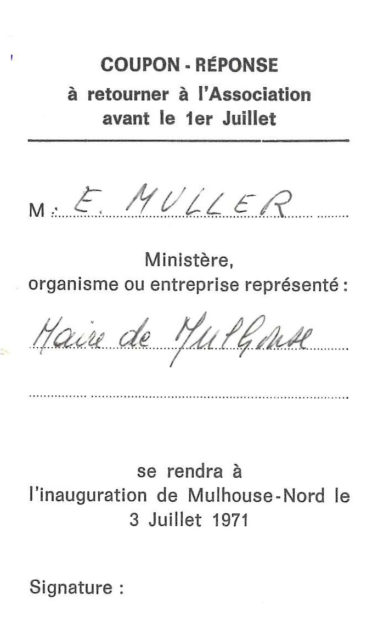

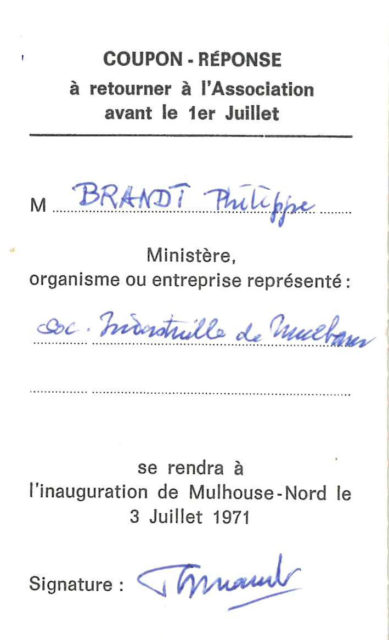

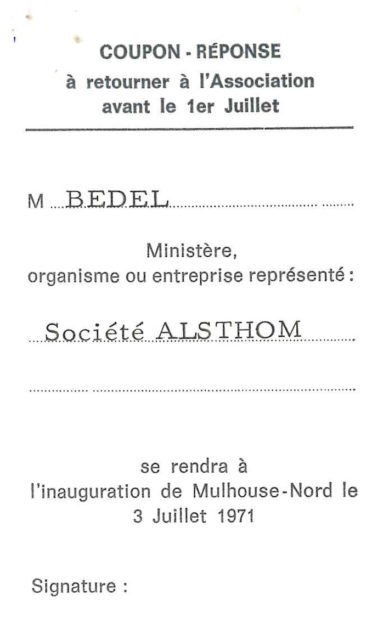

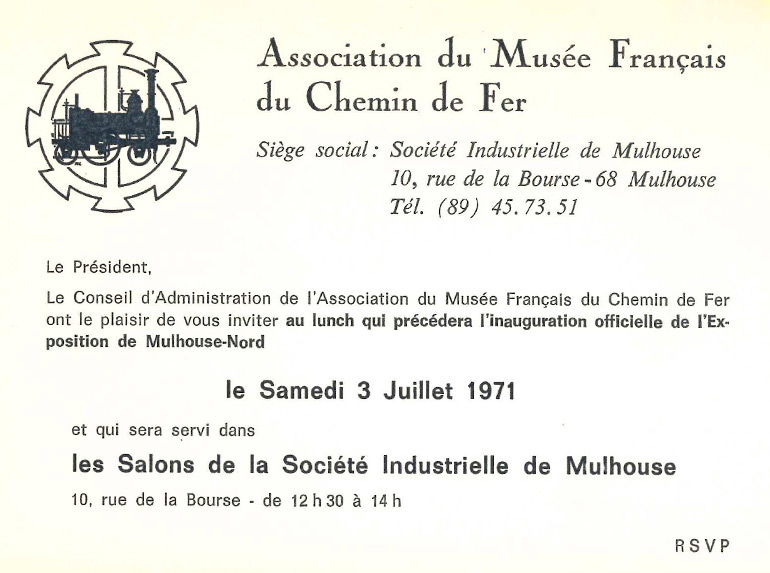

With their eyes turned up towards the entrails of the Pacific, or the cutaway view of the Baltic, as they listened to guides or wandered on their own, visitors of all ages discovered the French Railways Museum, or the MFCF as it is now known. Backstage, the museum staff were actively preparing another event: the official inauguration. The Cité du Train has kept the reply coupons, which are valuable traces of that time. Major figures of the French railways such as Marc de Caso or André Chapelon can be seen on these delicate pieces of card. A sheet that is laconically titled “Organisation” tells us about the high points of the day: lunch in the dining rooms of the SIM, speeches, tour of the city, receipt of railway handkerchiefs made specially for the occasion in partnership with the Fabric Printing Museum, not forgetting the young girls from Alsace who held in their hands a major symbol of the history of the museum – the inauguration ribbon.

The ribbon

is cut!

3 July 1971. 7 am Radios across the country were broadcasting news flashes of holiday traffic. As the hours went by, the motorways of Alsace filled up with motorists leaving the Vosges for their holiday destinations. In the offices of the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse and in the French Railways Museum, the atmosphere was just as feverish. They had to get everything ready for the official inauguration of the half roundhouse. On the Buddicom Saint-Pierre, the wooden lectern decorated with the arms of Mulhouse awaited its first speakers.

“[…] Of course, this final Museum will not house only steam locomotives: the first samples of electric and diesel traction will come here when they go out of service. And the powerful CC that is located before the roundhouse will one day become a relic of history, as will the Turbotrain. The vision of the past makes us turn our thoughts to the future. A remarkable conference recently addressed the state of the art in the year 2000. He concluded that the world population would reach 6 billion, that energy, while it was not rare, would have to be managed well, that 85% of the energy would take the form of electricity, that pollution control would become a pressing concern and that transport needs would continuously increase. The railways offer mass transport, which is extremely energy-efficient, and are particularly well suited to the use of electricity, which does not pollute. I would like to tell the founders of the French Railways Museum to leave room for expansion: the railways are only just starting out on their journey! ”

3 July 1971, speech by Chairman André Ségalat at the official inauguration of the French Railways Museum

7.47 am 500 kilometres away, in Paris, a group of people settled in carriage 15 of train 113 bound for Mulhouse. They included: André Ségalat, Chairman of SNCF, particularly accompanied by Mr Henri Lefort, Deputy General Manager, Mr Camille Martin, Equipment and Traction Manager and Mr Marcel Garreau, Honorary Director of SNCF.

12.08 pm Arrival in Mulhouse station. After lunch at the SIM, the officials were transferred by coach to Mulhouse-Nord.

2 pm The ceremony could start. Lit by the flashes of reporters for Loco-Revue or L’Alsace, Jean-Mathis Horrenberger spoke to the audience, followed by André Ségalat. The speech by the Chairman of SNCF still resounds within the walls of the Cité du Train. André Ségalat was optimistic and resolutely visionary, foreseeing the great issues of the third millennium as early as in 1971.

Art comes to the

Railways Museum

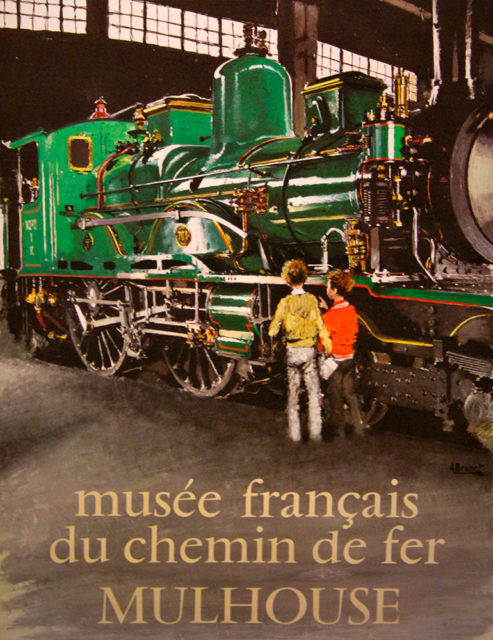

While the museum is a conservatory for rolling stock, it also aimed at preserving artistic representations of the railways. Even before the opening ceremony of June 1971, the museum took part in the Scheffer Prize, the 25th railways painting exhibition organised at the SIM. Less than a year later, with the support of the City of Mulhouse, the organisation purchased the collection of Charles Dollfus, an aviator who wrote much on the railways and possessed a rare series of decorative objects. At the same time, the painter Albert Brenet set up his easel before the Parthenay. This prolific artist, who had been commissioned by SNCF, put gouache onto the canvas for a preparatory sketch of the iconic poster of the French Railways Museum.

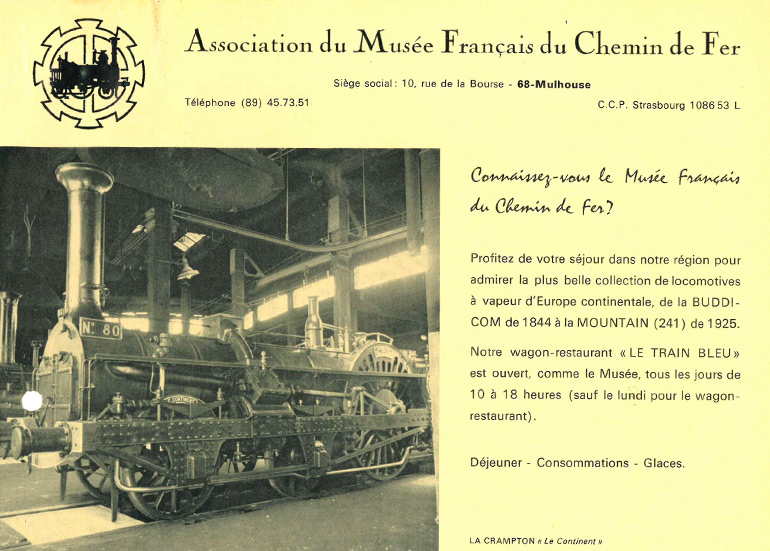

“Do you know

the French Railways Museum”

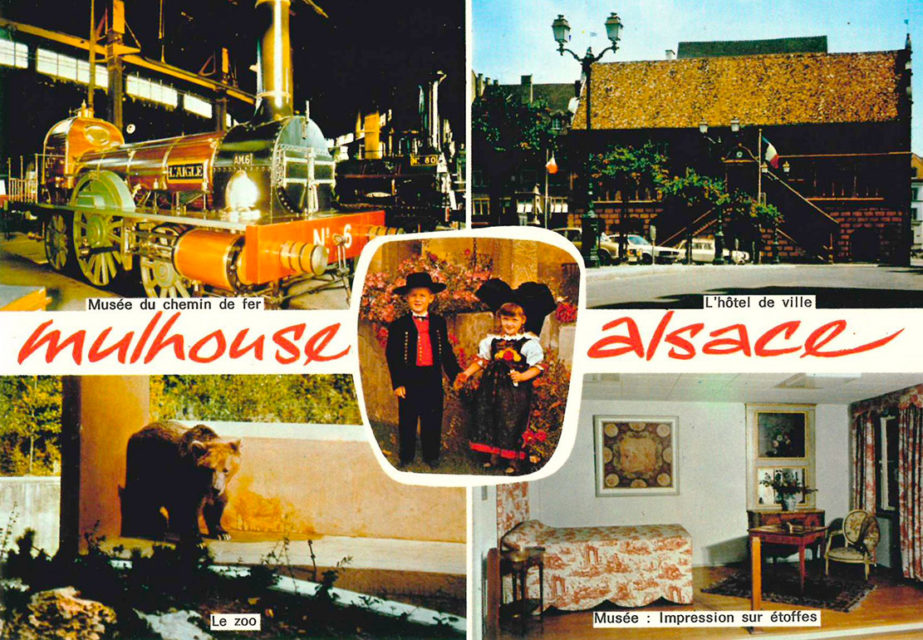

From the first years of the museum, its founders saw the need for publicising their establishment widely. Several thousand leaflets printed by L’Alsace on “90g cream-coloured coated paper” were handed out. But advertising had to be agreed by all, and the costs shared. On 25 November 1971, a meeting was organised to address the “coordination of propaganda between the different museums of Mulhouse”. The aim was to promote the cultural and tourist heritage of Mulhouse over a 150-km radius. A few months later, the counters of hotels, restaurants and tourist offices proudly bore brochures telling of the French Railways Museum, the Historical Museum, the Church of Saint-Stephen, the Fabric Printing Museum and the Zoo. But the efforts went further, and a need was felt to organise circuits between these major tourist sights. Coaches were supported by city buses. The employees were asked to promote the museum to day visitors and regular users alike. Because, in spite of the many advertising inserts and articles, word-of-mouth was still the best channel. However, glowing verbal recommendations may have been put in the shade by a legendary postcard, which was able to fit a train, a town hall, a bear, a period room and the whole essence of l’Alsace into 150 cm².

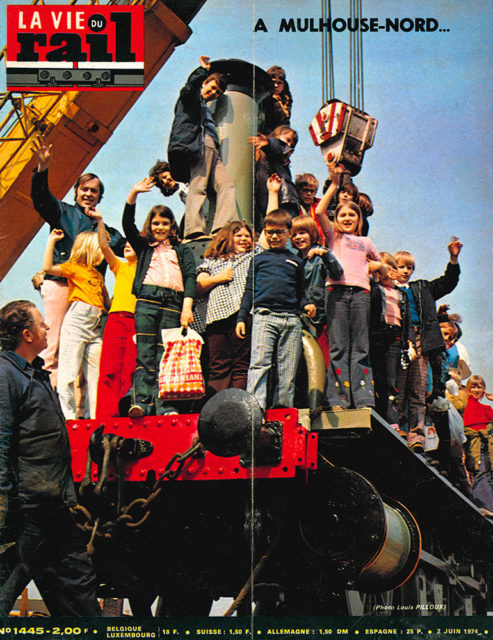

A locomotive

as the sign

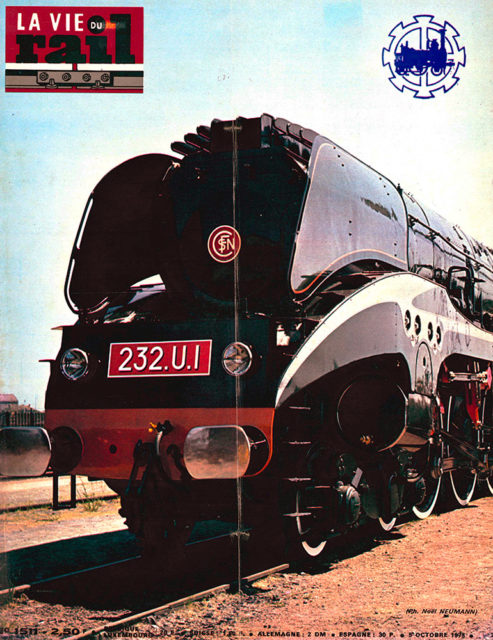

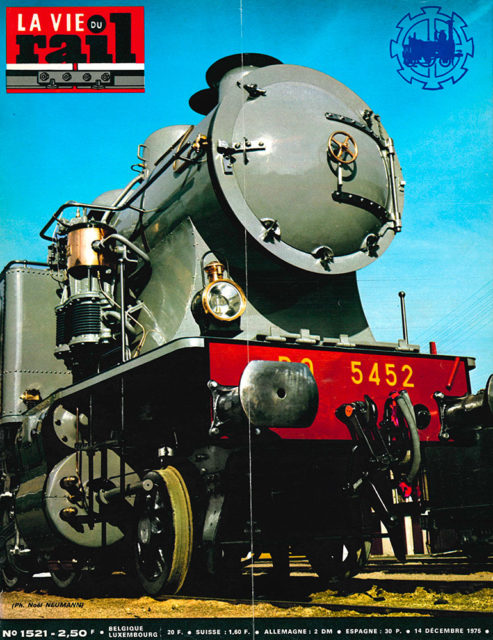

The leaflet, brochure, poster and postcard were not the only materials used. There was also the locomotive sign! In order to draw visitors to the museum from rue Josué Hofer, the Board of Directors rapidly approved the project of using scrapped equipment that was to be demolished as a life-size sign for the museum. In September 1972, Jean-Mathis Horrenberger thus informed André Portefaix, Chief Engineer, Traction and Equipment, of SNCF, of Michel Doerr’s wish to buy the 130 B 348, stabled in the Chaumont depot. The locomotive was described by the Chairman as having an “extremely characteristic figure”. The other advantage was that it weighed “only 48,500 kg”. Ultimately, the 030 TB 2 from the Arles workshop was selected. After its cabin and water tanks had been removed, this absurd machine left Provence for Romilly to be repainted. At the same time, Thouars offered to reconstruct the chimney. But the object alone could not be seen from the road. So it was given a plinth. On 1 April 1974, the makeshift loco left Romilly for Mulhouse. A few weeks later, the phone rang at 93 Avenue de Lutterbach, former headquarters of the lifting company Koenig. They were asked to lift the machine onto its narrow ballast. The operation, which the contractor described as “delicate”, was covered by La Vie du Rail, which applauded this “spectacular piece of handling”. A true little saga inside the wider story of the Museum, this episode gives an insight into how the establishment operated: an idea, partnerships between regions and in the end, children clambering on for a photo, even if that was not allowed!

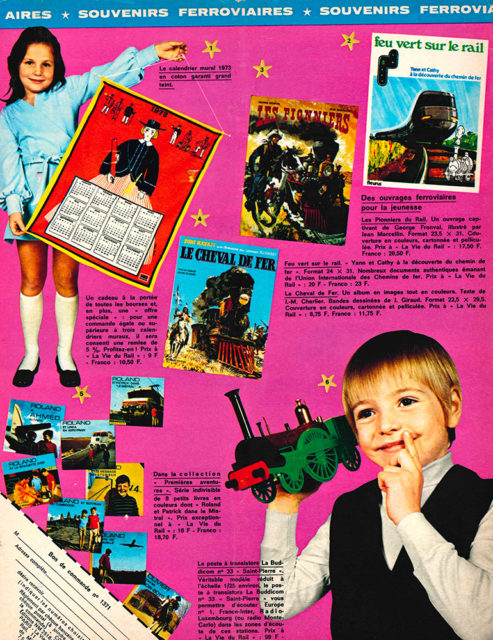

A passion for postcards

The postcards that were displayed on the cork board at the ticket office feature in the early minutes of the meetings of the board as “ancillary revenue’. By 1974, a sale kiosk was set up and they became a valuable source of additional revenue. A study of correspondence between 1971 and 1976 shows that the public were particularly keen on postcards. At the time, the idea of derivative products was new in the world of museums. At the National Museums Meeting, the sales department was set up in 1931, but it really took off in the 1970s. While it is not known whether the French Railways Museum drew on that model, it may be surmised that railways, nurtured by the imaginary world of toys and model trains, contributed to the phenomenon.

La Vie du Rail, the Epinal printer Pellerin, and the publishers La Cigogne and Dernières Nouvelles d’Alsace were some of the creative commercial partners. Postcards, stickers, slides, scrap books and cut-and-paste sheets were some of the souvenirs that visitors or contacts of the museum so liked. Michel Doerr then revealed his hand as a postcard strategist. In a letter to the Compagnie des Arts Photomécaniques of 1975, the Director defended the idea that the photograph of one of the locomotives should be framed so as to not include an “environment […] that is a fairly unattractive”.

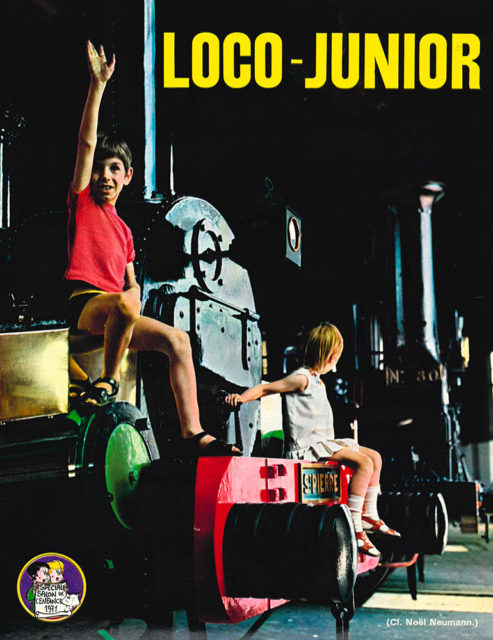

Children, and others

From the very beginning, the museum attracted railway workers, technicians, tourists, enthusiasts of fine objects, families and school groups. The archives of the 1970s are full of letters written in a child’s hand, from class representatives or teachers’ pets. To all these notes, Michel Doerr gave the same reply: “of course you can come and visit the museum with your class!” You were even advised to bring your own food, which you could eat under the parasols or in the restaurant car. A guide, slides and films were also available. Some items in the collection were educational, and reproduced in books for children. One of these is the Encyclopaedia in stamps: International locomotives and trains published in 1972 by Les Éditions des Deux Coqs d’Or. A small disc on the cover presented the book as “indispensable for all, boys and girls, who want to have fun as they learn , illustrate their books or make collections”.

“The little boy places a yellow cube behind a blue one and shouts in triumph: “A train”. Even after the moon landings, trains continue to enjoy a place in children’s imaginations, along with aeroplanes and cars.”

– Anonymous, excerpt from the article “The fascinating steam locomotives of the museum in Mulhouse” in L’Est Républicain, Nancy, no 490, 27 June 1971

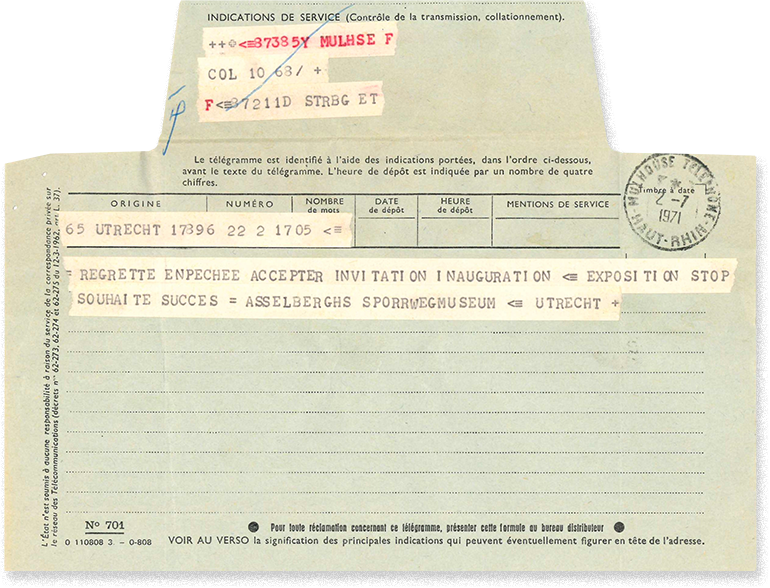

EXPOSITION – STOP – WISH YOU EVERY SUCCESS

In January 1970, in one of the pages of Towards a French Railways Museum, Michel Doerr and André Portefaix proposed a panorama of European railways museums. Their findings were clear: while Mulhouse was getting ready to open its museum, cities like Hamar, York, Nuremberg, Madrid, Copenhagen and Belgrade already had such institutions. Throughout their museum career, Jean-Mathis Horrenberger and Michel Doerr tirelessly devoted themselves to exchanging notes with them. For example, the Utrecht museum was invited to the inauguration of the half roundhouse in 1971.

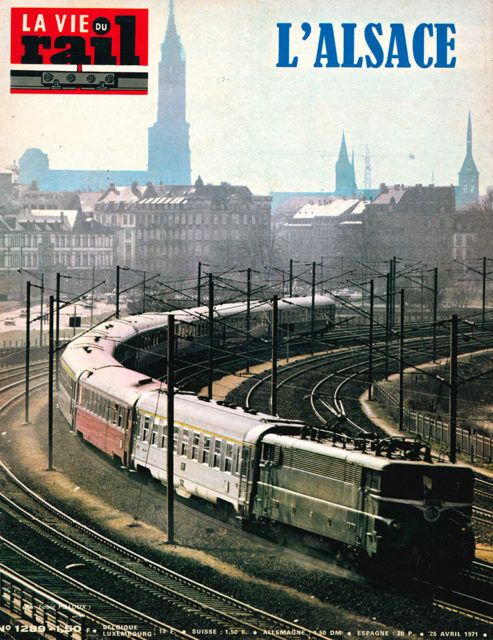

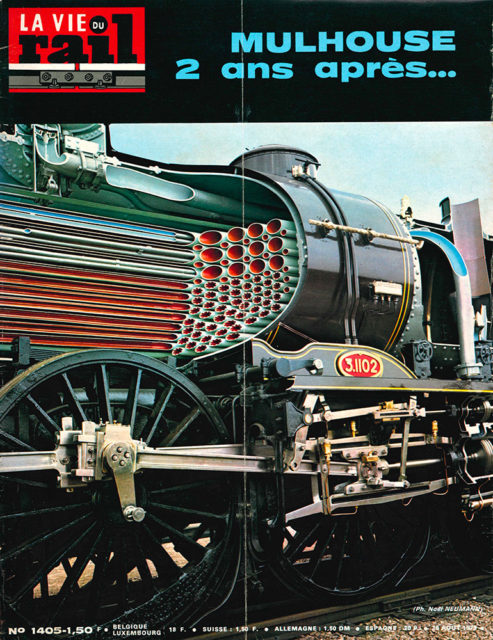

While life went on at the half roundhouse, local, national and specialised media were already devoting articles to the future permanent museum. Like a portrait gallery, the covers below take you back to the chronicles of the work being undertaken.

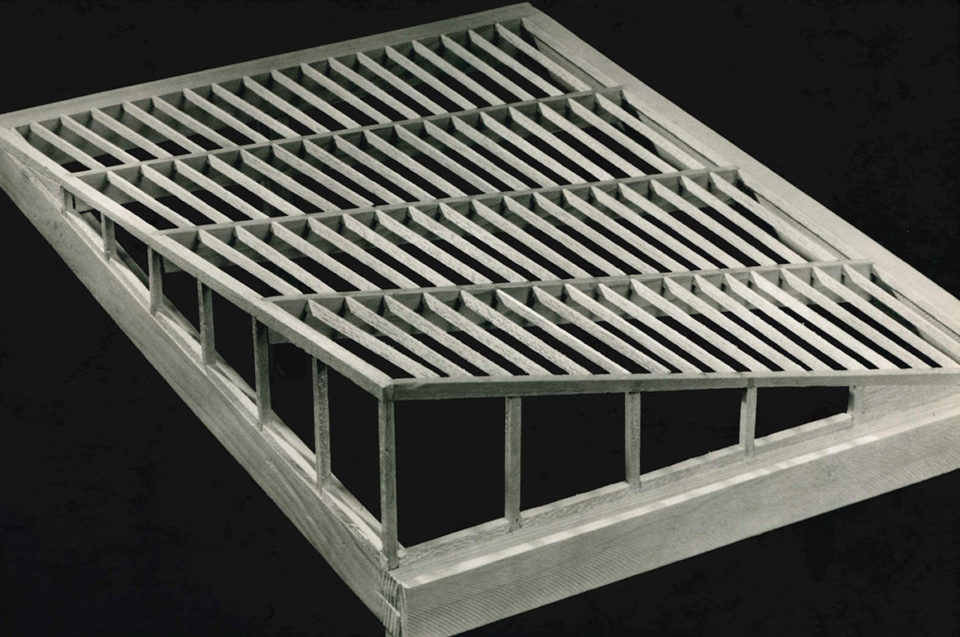

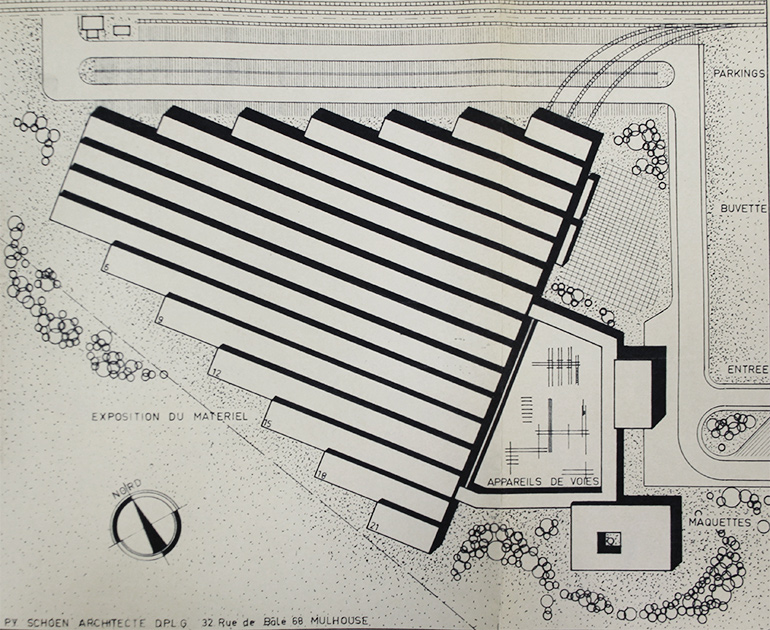

Wood and glumlam

From the beginning, the architect Pierre-Yves Schoen was informed by Jean-Mathis Horrenberger of the planned French Railways Museum in Mulhouse. He became a major player in its history. In October 1967, a meeting organised by the Committee for the creation of a French Railways Museum in Mulhouse set out a certain number of points. First of all, land would indeed be provided by the City of Mulhouse in the Mer Rouge district for the permanent building. The plans of that structure, which were already published in a newsletter of SIM, would include 35 tracks to display over 100 items. They would be supplemented by an area devoted to model trains and components. The idea of combining that early part with the creation of a museum devoted to fire fighters was also defended.

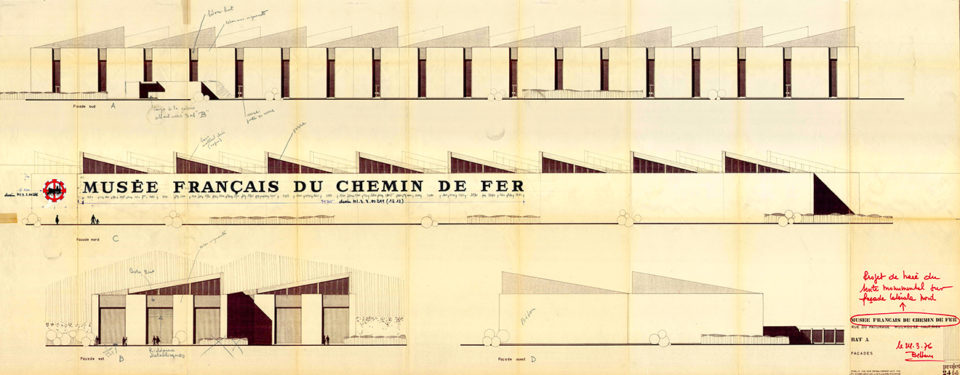

While some members and visitors were already nostalgic for the genuine railway atmosphere that had been made possible by a roundhouse, only the construction of a new building out of nothing could organise the flow of visitors and allow an extension of the collection. That setting, described as “unusual” by the architect, gave the pieces on display a more museum-like feel, and offered the possibility to create a large car park and a restaurant. While the construction of such support amenities was not out of the ordinary, that was not so of a museum devoted to trains. In May 1976, Pierre-Yves Schoen wrote an article in the Revue Générale des Chemins de Fer and explained that the first step would be to think of how the equipment would be brought to the site. That meant that the museum had to be built by a railway track, ideally supplemented by turntable, or transfer equipment. These solutions were found to be too expensive and were abandoned. The building was to be located on a triangular plot of land, so as to connect its internal tracks to the Strasbourg-Mulhouse track using a carefully calculated bend radius.

“To those constraints relating to the building site, were added those that I thought I knew but whose significance I had barely discovered. For instance, constraints due to the subject of the project: railways. To display a vehicle, you need 22 m x 9 m, that is above 200 m². In order to let the object “breathe”, the ceiling height has to be about 9 m. There must be enough light in the room, to allow photography. Visitors must get to see everything, top, bottom and sides, but must not be able to “touch”. Those are the broad outlines of the requirements for the exhibition room.”

– Pierre-Yves Schoen, document typewritten before the summer of 1971, Cité du Train collection

Inside the building, the requirements of conservation and display were also painstakingly studied. The constraints imposed by the size of trains were supplemented by those for photography. Even before the age of smartphones and social media, it was already obvious that visitors would want their souvenir photographs. The space therefore had to be bright and large. The “cost-effective and elegant” solution. The materials were selected with care: steel, wood and concrete were preferred. For example, the arcs that support the roof were designed using the principle of glulam wood.

In a letter sent in November 1969 to Michel Doerr, Pierre-Yves Schoen described this method as ideal, since it allowed “large spans with no support points, freedom to locate posts and fasten walkways at any point of the frame.” The main posts and beams were made in reinforced concrete. The façade was to be finished in Rhine pebble dash.

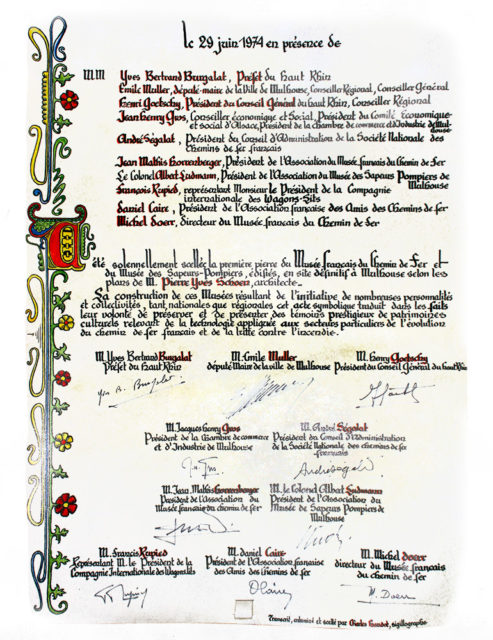

“This is the future location of THE FRENCH RAILWAYS MUSEUM”

The laying of the first stone, marking the official start of building work, was a high point in the history of the museum. The event, organised by the local contractor Savonitto, consisted firstly in clearing away, cleaning and top soil stripping. A block made up of a cast concrete stone was also made. Inside it, a piece of parchment for posterity was inserted during the ceremony of 29 June 1974. The document, which was signed at a meal organised at the restaurant in Mulhouse zoo, was found during work in the 2000s, and so reached us safely.

Publications about

the collection

In April 1975, the catalogue of the collection in the temporary exhibition of Mulhouse North was published. Richly illustrated with drawings by Michel Lamarche and E.A. Scheffer, the collection was characterised by original graphics aimed at highlighting the collection. It also provided an opportunity to briefly outline the history of railways and that of the museum. The concise text demonstrates the intention of addressing a wide public. Purchased by the Cité du Train in 2019, a version signed in 1975 by Michel Doerr is a nod to the future. The former Director was certain that the document would in a few years be part of the history of Alsace.

“In France, people believe that the public are not very open to issues relating to railways, which, they believe are an instrument of the past; however, when you see visitors crowding to have a close-up view of the equipment displayed, climb into cabs, pull the governor and operate the controller, one may ask whether the same public are really uninterested or if their indifference is not actually the result of a lack of opportunities to satisfy their curiosity…”

– Chemins de fer, no 134, May-June 1945, p.70

“I will go with it to the museum…”

Almost thirty years later, in July 1974, in a letter to the founders of the museum, a member of the organisation asked when the locomotive 232 U 1 would be displayed. The writer could be reassured since the locomotive, a masterpiece of the engineer Marc de Caso, was being given a complete refurbishment by workers in the Thouars workshop, and would be visible in the future museum. The film above was first screened in November 1975, taking its viewers behind the scenes, showing a project that would last two years.

The 232 U 1 was scrubbed and painted, bearing a whole section of the history of railways and their museum. In 1976, under the brand new structures of the new museum and thanks to the technical support of SNCF, the machine was put into motion without moving. Nearly fifty years on, this animation can still be seen in the museum.

Station to station

1976. The title track Station to Station on side A of the David Bowie album starts with the sound of a running train. Many miles away, between Mulhouse-North and Dornach, that mechanical melody echoed symbolically. As part of the opening at 2 rue Alfred de Glehn, the last items of rolling stock were leaving the half roundhouse. The end of an adventure? Oh no! The start of a new chapter, and mainly the entry into the new decade: that of the 1980s.

In a letter sent on 20 May 1976 to André Portefaix, Michel Doerr expressed his thanks for the “marvellous photos” brought by Mr Naudot, which “provide extraordinary memories of this roundhouse we are about to leave”. Moving a bit closer to the Vosges, the French Railways Museum ceased to be temporary and became final. And between the now bare walls of the depot, these words could be heard: “Here we are, one magical moment, such is the stuff, from which dreams are woven”.